Sunday, 20 September 2015

Find Your Dream Home - Polygon Searches

Polygon Searches

Swanage to the Solent

Highcliffe - of Selfridge Fame

Having recently put my home on the market, I started to think from the point of view of a purchaser about how my home could be more easily found?

It is pretty well known that there are a multitude of websites around that specialise in making available information about houses for sale and many offer various means to create (and save) search criteria.

Many estate agents have arrangements to provide details of the houses ‘on their books’ to one or more of these websites; for example, my estate agent, a branch of Winkworth, makes information available to Rightmove and Zoopla, amongst others.

By going to one of these sites on the internet, you can simply base a search on a location (village, city, postcode) and a radius (Immediate area, ¼ , ½, 1, 3, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30 or 40 miles) to create a search-circle. Additional criteria may include type of property, min &/or max price, min &/or max bedrooms, etc. as well as sort-style – lowest or highest price first.

Also, the choice of the initial display format - such as a (long) list of all properties meeting the criteria, a grid of properties with many more properties being shown per page for an easy, quick scan, or a display of the location of the property hits, on a zoom-able map.

The circle-search is fine for certain self-evident search requirements but for some situations, a more flexible kind of search may be more appropriate.

For instance, my home would be particularly of interest to firstly, those looking for a retirement home on the South coast, with the additional offering of extensive accommodation that might suite professional people requiring a consulting room with private entrance, or accommodation for an extended family.

A search that would help finding such a property is called a polygon search or Drawn Area (by Rightmove). This simply means that an area is drawn on a map by marking down points that result in a set of straight lines to eventually create a closed loop – termed in geometry, as a polygon. Once created, the points can be individually dragged to fine-tune the resulting search area.

Polygons can easily be created for unusual shapes such as coastal areas or strips, mountain valleys, parts of the Lake District or road corridors, like Salford or the M4, etc. All the other criteria, in this case 6 or more bedrooms, are simply applied to the polygon, rather than a circle, to produce the required hits. Finally, the search may optionally be saved with a descriptive name.

Here is an example below of a search to find 5+ bedroomed properties on the stretch of the South Coast between Swanage and the Solent. The fact that Highcliffe Castle is of Selfridge fame is not a valid criteria!

To do this using the more well-known circle search would either mean one very large circle with far too many unwanted hits away from the coast line, or a large series of small circles which would be time-consuming and very tedious to work with.

John Passmore, Rothesay Drive, Highcliffe, Dorset September 2015

Map View Results:

Grid View Results:

List View Results:

Panorama Views:

To view a search example in an internet browser, Link (Copy /Paste into browser or try Control/Click on this link):

http://www.rightmove.co.uk/property-for-sale/map.html?locationIdentifier=USERDEFINEDAREA%5E%7B%22id%22%3A3085445%7D&minPrice=900000&maxPrice=1250000&minBedrooms=5&displayPropertyType=houses&oldDisplayPropertyType=houses

Friday, 10 July 2009

THE CONTROL OF PERSONAL AND HOUSEHOLD FINANCES:

BALANCING THE DWBA STRUCTURE FOR BUDGETS AND MONITORING

INTRODUCTION

This blog continues the sequence of an on-going series of articles which is intended to provide summarised information about Domestic Well-Being (DWB) accounting.

The whole reason for implementing an accounting system is so that its user(s) can establish and achieve control of the underlying financial system being modelled. In this context, we are interested in the management and control of the finances of an individual or a domestic, household situation.

Prior to the previous blog which looked at the way-ahead for domestic accounting and which introduced the need for system providers to migrate from off-the-shelf personal accounting software packages to modern, Software as a Service (SaaS) server-based programs, I discussed the subject of DWBA reports.

This blog addresses the control of personal finances with an introduction to prototypes of some innovative new tools for dynamically creating budgets and monitoring financial activity against those budgets.

In more detail, these tools are intended to help obtain an optimum balance across the structure at the heart of the new DWB accounting model, develop corresponding budgets and to then monitor performance against those budgets. When required if things are not proceeding to plan, it would be necessary to simply repeat the budget cycle as often as needed but typically, at 3-monthly quarters.

REPORTS

The main report for control purposes is the Domestic Well-Being Statement (DWBS). This report, replacing the business-style Trading and Profit & Loss reports, details the changes that may have occurred over the previous financial period, typically 1, 3, 6, 9 or 12 months – but the longer the better.

You will recall from earlier blogs that this report represents the hierarchical DWB structure with categories and levels of sub-categories for both the Increases and Decreases to the finances that may have occurred over some period.

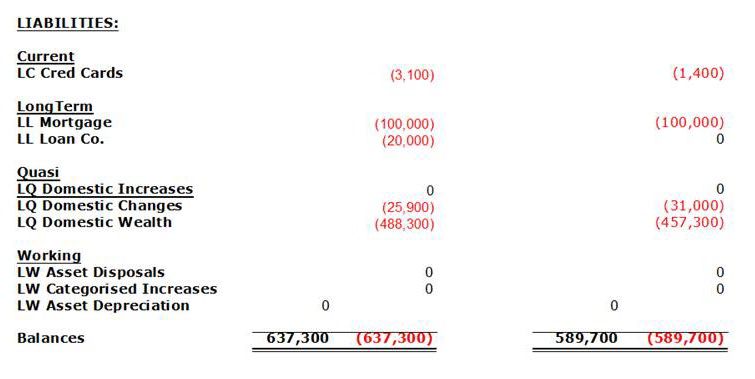

Another report, the Domestic Balance Sheet (DBS) gave us the static information about our various assets and liabilities of different types on a particular day, usually the last day of the period. The changes over a period obtained from the DWBS, equate to the overall change in the static financial position occurring between the beginning and the end of that period under consideration.

Let’s now look at some views of the DWBS where we are looking at the changes that were recorded from transactions in a sample, year’s worth of financial data used as the example set of accounts for my book ‘Accounting for a Better life’.

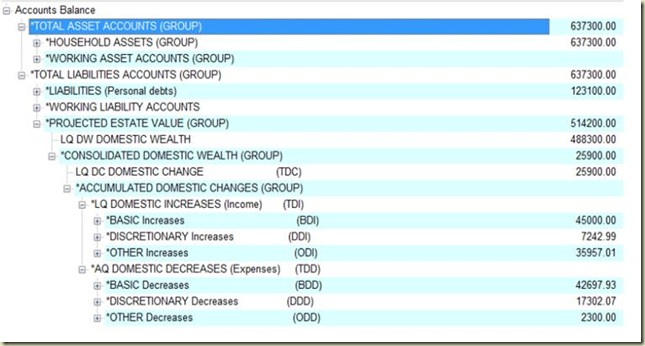

The images you see are from an implementation of the DWB accounting model in an off-the-shelf accounting package called Personal Accountz©. This first view shows the top level of the changes that have occurred over the year:

The first six rows are about the static elements of our financial situation – our assets and personal liabilities or debts – plus some so-called temporary working accounts used to mediate certain financial activity.

Next, we have the projected value of our estate, made up of our Domestic Wealth as at the last time we recorded it – at the beginning of the current period - plus the accumulated changes during the current period. You can see that the Total Domestic Change (TDC) is £25,900 made up of two groups, for Increases (LQ Domestic Increases) and Decreases (AQ Domestic Decreases); the + signs indicate that there is more detail available at lower sub-category levels.

The prefixes LQ and AQ stand for quasi-liabilities and quasi-assets, respectively; where these account name prefixes are discussed in a previous blog on ‘DWBA Accounting – Some Theory’.

The totals of the increases and decreases are not visible here because their values of £88,200 and £62,300 respectively have already been moved to the TDC account giving us the difference, being a surplus value of £25,900. I call this a Domestic Surplus (Domplus), in contrast to a Domestic Deficit (Domicit) when the decreases would have exceeded the increases over some period. This is the domestic or household equivalent of business profit or loss.

If we click on the two + tabs against Increases and Decreases, we see the next lower levels of the DWB structure with the sub-totals for the Basic, Discretionary and Other (non-Discretionary) categories for each of them.

Now we can begin to see the high-level balance, or perhaps lack of balance, in the structure of a year’s worth of personal or household financial activity – a high value for ‘Other’ Increases and relatively low ‘Discretionary’ Decreases.

A BALANCING TOOL

Once the figures for a past complete or part-period have been examined, what was needed was an easy and visually appealing way to undertake the balancing process for the next period. A prototype balancing and budget creation tool has now been added to the DWB accounting model repertoire that does just that.

The way the new tool works is by overlaying a series of adjustable bars, on top of bar charts for the figures accumulated for the previous or current period. The required Balance amongst the categories for a new budget can be achieved by simply adjusting the length of the various bars in an iterative way, compared to those of the previous period.

Without knowing too much yet about the significance of Basics, Discretionary and Others, separately for both the Increases and Decreases, we have the first indication of what the current balance at the end of the last period looks like. Having said looks like, a picture will give us a better view so here is a bar chart view of what we have seen and know so far from the DWBS report:

This overview-level view shows how the totals for the Increases (blue) and Decreases (red) for an accounting period are made up and what the relative distribution looks like amongst those top-level DWB Categories. The green bars are for our new planned budget arrangement, hopefully adjusted to achieve the best possible DWB balance.

The heading shows us that we are looking at values for the past 12 months for our ‘Last Period’ so we are looking at the situation at the end of a 12-month period where we might be developing a budget for the next 12 months.

All the values associated with each of the bars are shown at the end of each bar as both an actual value (the first figure – in whatever currency - £ here), as well as this value in a normalised format, as the second figure.

For the normalised values, the higher of the totals for the Increases or Decreases amounts are associated with 1.0 and all the other displayed values are therefore shown as a proportion of 1.0; so for these DWB example figures, the Increases were higher than the Decreases so the Increases total of £88,200 is equated to 1.0 and the Decreases of £62,300 therefore can be seen to have a normalised value of 0.71 and all the other normalised bar values are displayed accordingly.

Normalisation gives us a quick way to see relative differences between the values – if you prefer percentages, just mentally multiply the normalised values by 100. What we see here is that the Decreases were about 70% (0.71) of the Increases during the last period.

At this point at the end of one period, we would probably be interested in deciding what changes we might we wish to see by the end of the next period, in a years time. Let’s look further at the tools at our disposal.

The new objects are a series of ‘sliders’ associated with some new bars shown in green in these views. The sliders can be grabbed and moved with a mouse or clicked on the arrow-heads at either end of the slider to achieve more controlled incremental changes in the amount and length of each of their linked bars.

Some of the green bars representing totals for subordinate groups of bars are not associated with sliders themselves but move to show the accumulated effect of moving sliders in the subordinate bars that are contained in their represented totals.

There are movable bars for the main DWB Categories for both the Increases and the Decreases where the purpose at this overview-level is to make changes for the future desired amounts of the particular quantities associated with each bar.

For example for Increases, there may be a known salary increase expected so this can be factored into the Basic Increases for next year or for the remainder of the current period if we are re-balancing some way into a period.

With knowledge of the details of what happened last year, you would know that the relatively high amount of Other Increases last year was due to an inheritance from Uncle Jo and so the projected amount for Others for next year can be correspondingly reduced with little likelihood of another inheritance.

As changes are made to the lower, more detailed levels for Basic, Discretionary and Others, the corresponding Totals bars will also change in amount and length, dynamically.

At this overview-level, the issues will be about the relative balance or proportions of the desired amounts for the three DWB Categories making up Decreases – Basics, Discretionary and Others (non-Discretionary). These will be viewed in relation to last year’s amounts, the likely Increases for next year and the resulting Domplus or Domicit that can be accepted or is desired for next year.

In contrast to maximising profits in business, our domestic life seeks only a modest and steady increase in Domestic Wealth but from the DWB perspective, we look for a better balanced set of financial decreases to ensure that the best possible ‘life’ is being experienced within the applicable constraints.

The predicted wealth based on our developing budget can be seen from the moving, Total Domestic Change (TDC) bar, included at the top and bottom of the complete chart. Here, the projected figures for the TDC for next year is highlighted; this is shown in comparison to the static bar/figure for last year, and where the TDC for next year can be seen to change as the projections are being made with the sliders for the Increases and Decreases for next year.

Other overview-level inputs that maybe appropriate, result from decisions made in respect of reducing any existing debt over the coming year and the need for any new, short to medium-term savings, over and above regular provisions for the future, hopefully managed under the Investment for the Future (IFF) sub-category.

From the static data in the DBS, also visible on the main Accountz screen, the level of personal current debt accumulated might be considered unacceptably high and a decision made to reduce it by some achievable amount, over the forthcoming period.

The planned re-payments to do this over the coming period will have to be balanced alongside all the other decreases earmarked for the next period and the selected future target reduction in personal debt should therefore be entered using one of the two bars, under Discretionary Balancing.

Any need for a particular accumulation of funds as short to medium-term savings, to replace an old car for example, should be entered with the second bar at this level, under Discretionary Balancing.

As you progress down to the lower levels of the balancing process, difficulties discovered in achieving a workable balance at the lower levels may well require a return to either or both the intermediate and top levels to alter some previously chosen values. The very nature of the hierarchical description of the characteristics of financial behaviour behind the DWB structure implies that an iterative process will be required to achieving an optimal balance.

Each adjustable bar used for planning future financial activity is identified with characters relating to its sub-category identity e.g. ‘D’ for debt; ‘S’ for savings and ‘1F’ for Car1 Fuel. There is also an additional pair of numbers at the end of some of the planning bars; these represent the annual and monthly future change compared to the previous period, required for this sub-category in order to achieve the new amount of increase or decrease represented by the length of the particular bar. This number changes dynamically as the length of each bar is adjusted and similar changes are reflected in the figures of associated higher-level Totals.

Colour as mentioned earlier is also used to help distinguish particular types of bar – blue for previous period increases, red for previous level decreases, green for selected budget values for the next period and blue for values previously selected/budgeted at higher levels of the iterative budget creation process.

The target to be met by balancing lower level sub-categories at any particular level of balancing is therefore the blue bar amount shown at this level, established by previous balancing at the next higher level.

Returning to the DWBS, we need to expose some lower levels of detail so here is another view with the next lower level of sub-categories for the Increases, opened up:

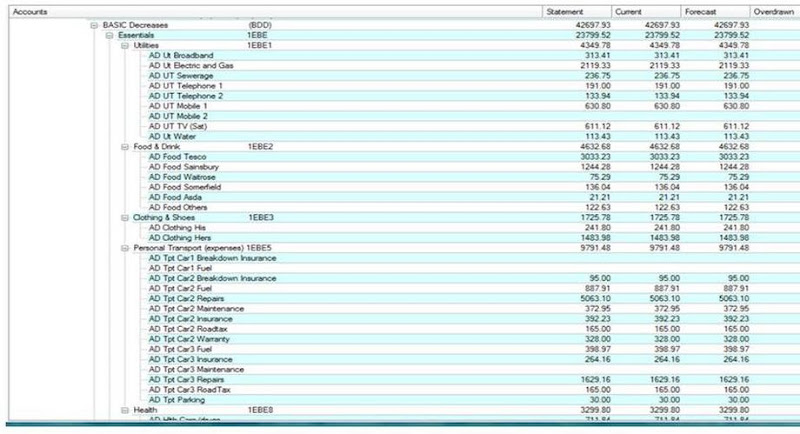

Now let’s look at more detail for the Decreases for the current period – already with some of the intermediate levels of the DWB structure visible:

Here we can see the two main sub-categories of Basic Decreases, the Essentials and Responsibilities with their next, lower-level sub-categories.

We can of course keep on drilling down to see more and more detail, right down to individual financial transactions.

The power of this structure and the resulting figures for some reporting period mean that we now have a basis for quite detailed decision-making for the future.

The whole concept behind DWB accounting is towards achieving the best possible balance of personal or household finances and hence, achieving a better life within the prevailing constraints.

By this, we want to get a proper balance across all the categories of expenses. We want to avoid spending excessively in some areas to the detriment of spending in other areas.

By ensuring that we spend proportionately in all areas, the implication is that we should experience a better overall life since we should be obtaining the benefits and rewards of all the many categories of purchased produce, items and activities that make up the typical, day-to-day lifetime experience.

The DWBS figures enable us to search for balance and as we are seeing, dynamically alter how we want this balance to look for the future.

This will always be in order to obtain the best possible balance within the prevailing constraints. These constraints as we have seen are essentially the increases, as income, together with any existing debt that needs to be reduced and any new requirement to accumulate particular amounts as savings for short to medium-term financial priorities – e.g. that car replacement.

After that, the priorities are first, to make sure that for the Decreases, care is taken of the Basics in terms of both the Essentials (food, clothing, accommodation, utilities, etc.) and the Responsibilities that we all experience - such as taxes, household obligations, professional expenses, garden maintenance, etc.

Next, at the Discretionary category of Decreases we should ensure that we have equitable and balanced expenditure across the Nice-to-Have’s of Holidays, Leisure and Entertainment, and Hobbies; as well as the all-important, Investment for the Future (IFF).

With the likelihood of an ever-inadequate future pension, it is even more important that everyone makes their own adequate additional provision for the future. This means ensuring that appropriate amounts are stored away or invested on a regular basis and it is common knowledge that the earlier the start is made, the easier the process and the greater the future pension or provision for the future is likely to be.

DWB addresses amounts to save but specialist advice would be required on the choice of investments and how best to benefit from such investment in practise.

As ‘balancing’ decisions are made at the higher levels of the structure, it will then be necessary to go to the lower-level sub-categories to determine what more detailed changes need to be made at these lower levels and below, by balancing in more detail, in order to achieve the balance envisaged by the top-level decisions.

As we have begun to see, it turns out to be an iterative process where difficulties might be discovered in achieving the required balance at the lowest levels. This usually implies a return to the intermediate or top levels for possible further redistribution across the sub-categories, or even to go back to the overview-level to accept and to readjust those amounts accordingly. This is because these first-cut high-level targets might now appear unachievable in practice when balancing at all levels has been attempted.

Understandably, you cannot try to achieve the impossible. Your desired balance within all the levels have to match the likely Increases. Of course you might well conclude that you need more qualifications and a better job to achieve the lifestyle to which you aspire! This is just another feature of the visibility on your finances provided by the DWB accounting model.

BUDGETS

In general, what we are trying to do is to work out what we would like the future figures at the end of some period, to look like. Budgets are lists of figures or targets for financial activity, most often for expenditure, and will be most useful if these figures can estimate target amounts at varying future points – say 3-months, 6-months, 9-months and on to the end-of-year, 12 months ahead.

The main by-product of the new structured, dynamic balancing tool is a set of budget amounts for every sub-category of the DWB structure, at all of the required, future 3-month quarterly points.

Obviously for a home or domestic situation, we do not want to overdo things by trying to control everything in too much detail so it will be important for users to select for actual control purposes, just the figures for the sub-categories for budgetary control that have the most impact. By this, we need to concentrate on making decisions on trying to reign-in spending in areas that we find are in most need of cutbacks or for re-balance.

We also need to try to control areas where there is an element of flexibility or choice to make it possible to actually achieve the implied future changes through corresponding changes in spending patterns (with appropriate self-control and discipline!). This might involve deliberate decisions to cut back on some utilities, car usage, food costs, luxuries and so on.

Let’s now look at some of the lower levels of the balancing process. There are four levels of balancing available with DWB to be used as needed and not every sub-category of Decreases will be expanded to be balanced in detail at the level in which it lies:

Overview level

Top level

Intermediate level

and Low or Bottom level

We have so far looked at the Overview level where those general decisions were made in regard to likely future Increases and the desired distribution and amounts of future Decreases at the major category level.

The next three levels only address Decreases as there is very little more to be said or controlled at the lower level, DWB sub-categories for Increases.

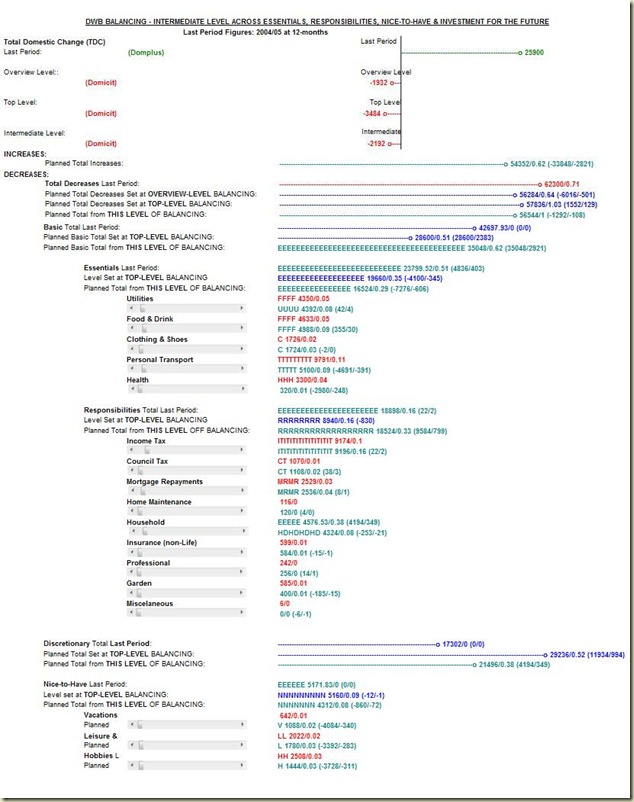

Here is the balancing tool being used at the Top level, for Decreases:

The new objects are a series of ‘sliders’ associated with some new bars shown in green in these views. The sliders can be grabbed and moved with a mouse or clicked on the arrow-heads at either end of the slider to achieve more controlled incremental changes in the amount and length of each of their linked bars.

Some of the green bars representing totals for subordinate groups of bars are not associated with sliders themselves but move to show the accumulated effect of moving sliders in the subordinate bars that are contained in their represented totals.

There are movable bars for the main DWB Categories for both the Increases and the Decreases where the purpose at this overview-level is to make changes for the future desired amounts of the particular quantities associated with each bar.

For example for Increases, there may be a known salary increase expected so this can be factored into the Basic Increases for next year or for the remainder of the current period if we are re-balancing some way into a period. With knowledge of the details of what happened last year, you would know that the relatively high amount of Other Increases last year was due to an inheritance from Uncle Jo and so the projected amount for Others for next year can be correspondingly reduced with little likelihood of another inheritance.

As changes are made to the lower, more detailed levels for Basic, Discretionary and Others, the corresponding Totals bars will also change in amount and length, dynamically.

At this overview-level, the issues will be about the relative balance or proportions of the desired amounts for the three DWB Categories making up Decreases – Basics, Discretionary and Others (non-Discretionary). These will be viewed in relation to last year’s amounts, the likely Increases for next year and the resulting Domplus or Domicit that can be accepted or is desired for next year.

In contrast to maximising profits in business, our domestic life seeks only a modest and steady increase in Domestic Wealth but from the DWB perspective, we look for a better balanced set of financial decreases to ensure that the best possible ‘life’ is being experienced within the applicable constraints.

The predicted wealth based on our developing budget can be seen from the moving, Total Domestic Change (TDC) bar, included at the top and bottom of the complete chart. Here, the projected figures for the TDC for next year is highlighted; this is shown in comparison to the static bar/figure for last year, and where the TDC for next year can be seen to change as the projections are being made with the sliders for the Increases and Decreases for next year.

Other overview-level inputs that maybe appropriate, result from decisions made in respect of reducing any existing debt over the coming year and the need for any new, short to medium-term savings, over and above regular provisions for the future, hopefully managed under the Investment for the Future (IFF) sub-category.

From the static data in the DBS, also visible on the main Accountz screen, the level of personal current debt accumulated might be considered unacceptably high and a decision made to reduce it by some achievable amount, over the forthcoming period.

The planned re-payments to do this over the coming period will have to be balanced alongside all the other decreases earmarked for the next period and the selected future target reduction in personal debt should therefore be entered using one of the two bars, under Discretionary Balancing.

Any need for a particular accumulation of funds as short to medium-term savings, to replace an old car for example, should be entered with the second bar at this level, under Discretionary Balancing.

As you progress down to the lower levels of the balancing process, difficulties discovered in achieving a workable balance at the lower levels may well require a return to either or both the intermediate and top levels to alter some previously chosen values. The very nature of the hierarchical description of the characteristics of financial behaviour behind the DWB structure implies that an iterative process will be required to achieving an optimal balance.

Each adjustable bar used for planning future financial activity is identified with characters relating to its sub-category identity e.g. ‘D’ for debt; ‘S’ for savings and ‘1F’ for Car1 Fuel. There is also an additional pair of numbers at the end of some of the planning bars; these represent the annual and monthly future change compared to the previous period, required for this sub-category in order to achieve the new amount of increase or decrease represented by the length of the particular bar. This number changes dynamically as the length of each bar is adjusted and similar changes are reflected in the figures of associated higher-level Totals.

Colour as mentioned earlier is also used to help distinguish particular types of bar – blue for previous period increases, red for previous level decreases, green for selected budget values for the next period and blue for values previously selected/budgeted at higher levels of the iterative budget creation process.

The target to be met by balancing lower level sub-categories at any particular level of balancing is therefore the blue bar amount shown at this level, established by previous balancing at the next higher level.

Returning to the DWBS, we need to expose some lower levels of detail so here is another view with the next lower level of sub-categories for the Increases, opened up:

Now let’s look at more detail for the Decreases for the current period – already with some of the intermediate levels of the DWB structure visible:

Here we can see the two main sub-categories of Basic Decreases, the Essentials and Responsibilities with their next, lower-level sub-categories.

We can of course keep on drilling down to see more and more detail, right down to individual financial transactions.

The power of this structure and the resulting figures for some reporting period mean that we now have a basis for quite detailed decision-making for the future.

The whole concept behind DWB accounting is towards achieving the best possible balance of personal or household finances and hence, achieving a better life within the prevailing constraints.

By this, we want to get a proper balance across all the categories of expenses. We want to avoid spending excessively in some areas to the detriment of spending in other areas. By ensuring that we spend proportionately in all areas, the implication is that we should experience a better overall life since we should be obtaining the benefits and rewards of all the many categories of purchased produce, items and activities that make up the typical, day-to-day lifetime experience.

The DWBS figures enable us to search for balance and as we are seeing, dynamically alter how we want this balance to look for the future.

This will always be in order to obtain the best possible balance within the prevailing constraints. These constraints as we have seen are essentially the increases, as income, together with any existing debt that needs to be reduced and any new requirement to accumulate particular amounts as savings for short to medium-term financial priorities – e.g. that car replacement.

After that, the priorities are first, to make sure that for the Decreases, care is taken of the Basics in terms of both the Essentials (food, clothing, accommodation, utilities, etc.) and the Responsibilities that we all experience - such as taxes, household obligations, professional expenses, garden maintenance, etc.

Next, at the Discretionary category of Decreases we should ensure that we have equitable and balanced expenditure across the Nice-to-Have’s of Holidays, Leisure and Entertainment, and Hobbies; as well as the all-important, Investment for the Future (IFF).

With the likelihood of an ever-inadequate future pension, it is even more important that everyone makes their own adequate additional provision for the future. This means ensuring that appropriate amounts are stored away or invested on a regular basis and it is common knowledge that the earlier the start is made, the easier the process and the greater the future pension or provision for the future is likely to be.

DWB addresses amounts to save but specialist advice would be required on the choice of investments and how best to benefit from such investment in practise.

As ‘balancing’ decisions are made at the higher levels of the structure, it will then be necessary to go to the lower-level sub-categories to determine what more detailed changes need to be made at these lower levels and below, by balancing in more detail, in order to achieve the balance envisaged by the top-level decisions.

As we have begun to see, it turns out to be an iterative process where difficulties might be discovered in achieving the required balance at the lowest levels. This usually implies a return to the intermediate or top levels for possible further redistribution across the sub-categories, or even to go back to the overview-level to accept and to readjust those amounts accordingly. This is because these first-cut high-level targets might now appear unachievable in practice when balancing at all levels has been attempted.

Understandably, you cannot try to achieve the impossible. Your desired balance within all the levels have to match the likely Increases. Of course you might well conclude that you need more qualifications and a better job to achieve the lifestyle to which you aspire! This is just another feature of the visibility on your finances provided by the DWB accounting model.

BUDGETS

In general, what we are trying to do is to work out what we would like the future figures at the end of some period, to look like. Budgets are lists of figures or targets for financial activity, most often for expenditure, and will be most useful if these figures can estimate target amounts at varying future points – say 3-months, 6-months, 9-months and on to the end-of-year, 12 months ahead.

The main by-product of the new structured, dynamic balancing tool is a set of budget amounts for every sub-category of the DWB structure, at all of the required, future 3-month quarterly points.

Obviously for a home or domestic situation, we do not want to overdo things by trying to control everything in too much detail so it will be important for users to select for actual control purposes, just the figures for the sub-categories for budgetary control that have the most impact. By this, we need to concentrate on making decisions on trying to reign-in spending in areas that we find are in most need of cutbacks or for re-balance.

We also need to try to control areas where there is an element of flexibility or choice to make it possible to actually achieve the implied future changes through corresponding changes in spending patterns (with appropriate self-control and discipline!). This might involve deliberate decisions to cut back on some utilities, car usage, food costs, luxuries and so on.

Let’s now look at some of the lower levels of the balancing process. There are four levels of balancing available with DWB to be used as needed and not every sub-category of Decreases will be expanded to be balanced in detail at the level in which it lies:

Overview level

Top level

Intermediate level

and Low or Bottom level

We have so far looked at the Overview level where those general decisions were made in regard to likely future Increases and the desired distribution and amounts of future Decreases at the major category level.

The next three levels only address Decreases as there is very little more to be said or controlled at the lower level, DWB sub-categories for Increases.

Here is the balancing tool being used at the Top level, for Decreases:

At this Top level below the Overview-level, we examine the past amounts spent and the distributions across the Basic sub-categories of Essentials and Responsibilities, and the Discretionary sub-categories of Nice-to-Have, Investment for the Future (IFF), Luxuries and a catch-all of Miscellaneous Disposals; for example we may have decided next year that a major gift is to be made, perhaps for a forthcoming wedding.

Here is an example of the results of Intermediate-level balancing:

At the Intermediate level, we begin to try to achieve a balance within certain of the sub-categories that we balanced at the Top level. For example, for the Essentials category, we try to achieve a balanced spread of planned decreases for the sub-categories comprising Essentials (Utilities, Food & Drink, Clothing & Shoes, Personal Transport expenses and Health) that equals the value selected for Essentials at the higher (Top) level.

At the lower levels, only a few and appropriate sub-categories would be subject to detailed balancing. These could include Utilities and Transport from Basic/ Essentials, and Leisure and Entertainment, and Hobbies from Discretionary/ Nice-to-Have, because these are areas which are more amenable to detailed control over the coming period, through active expenditure control.

This screen shot illustrates the sliders used to balance the Utilities and Transport expenses sub-categories of the Essentials sub-category of the Basic decreases:

The starting points for decision-making and hence budget preparation regarding future financial activity vary from a start-up position where no previous figures are held, right through to the start of a new period (financial or calendar year perhaps) where all the figures for the previous period have been retained. This is the situation we have been looking at above.

Intermediate between these two extremes will be the situation where some figures for the previous quarter(s) perhaps or where a particular number of days have elapsed since data accumulation first started.

Where part-period figures are held, they can be scaled-up by the tool to the end of the current period. In this way although not completely accurate, we can see how, based on figures to-date, we might be likely to ‘do’ by the end-of-period if nothing changed.

A budget produced from these figures will be more meaningful than one produced from a complete guess. Obviously as time goes by and more figures are accumulated, a new budget creation exercise will benefit from less scaling-up and therefore more accurate, likely target figures for the remaining time to the end of the current period.

The balancing process can be extremely quick to complete and considering that it would only need to be undertaken periodically, at say 3-monthly intervals, it is hardly a demanding overhead.

Here are the budget results obtained after balancing has been completed. It shows sample budget figures available for whatever purpose the user wishes:

Typically, selected values would be inserted into the user’s accounting package so that as time progresses, the actual figures accumulated could be compared to the pre-set budget quantities so that alarms would be triggered where deviations from the desired expenditure amounts were detected.

Budgets could be set not only for categories of expenses, as decreases, but also for credit card balances to warn against exceeding pre-set debt limits. It would be pointless to save in order to cut down existing debt levels whilst incurring additional debt with over zealous credit card usage.

By saving sets of planned budget settings based on this slider-based balancing process, comparisons can be undertaken in the future with this tool through monitoring. This is done by overlaying the budget figures with the actual recorded expenditure figures. If appropriate, a new budget can be created to provide new projected figures whenever needed.

MONITORING PROGRESS

As we progress through the next financial period it will be helpful once budget figures are set, if we can see how we are doing in relation to those target figures. How you accomplish this will depend on the details of your accounting package but most good systems allow you to enter pre-set budget figures.

By establishing intermediate check-points at those 3-monthly intervals perhaps, we will be able to determine if we are on-track, need to do better, or perhaps have done rather better than expected in some areas and hence have an opportunity to re-adjust our budget figures for the next interval by revising the budget creation exercise. In this way, areas that were proving difficult to keep to budget might be given more leeway from surpluses found in other areas so that the overall target might still be achieved with focussed re-planning along the way.

Another version of the balancing tool can be used to assist the monitoring process and is not associated with any budgeting controls that may be available as part of the accounting package used. The two overlaid sets of bars in this monitoring chart enable comparison of a saved set of budget amounts with the actual state of real increases and decreases as accumulated in the accounts.

Areas where attention will be needed will be obvious, either with the need for stricter adherence to the existing plan, or possibly a re-planning exercise leading to a modified set of budget figures for the remainder of the period.

The next screenshots show the monitoring with budget figures including the quarter points (1, 2, 3 and 4) in blue with the corresponding actual figures below each blue bar, in green. Sliders are interspersed amongst the bars to facilitate dynamically changing the scales of the bars in groups, to make interpretation as easy as possible with the varied range of values to be displayed. The actual figures in these images are as-at the end of the First quarter so we would be looking for correspondence between budget and ‘Actuals’ at the ‘1’ in the blue budget bars.

The only real concerns in this example which would require further investigation would be the high value for car maintenance in Personal Transport expenses which puts the Basic/Essentials, over-budget. Knowing about the finances, we would be aware that this was due to an unexpectedly high bill for car repairs!

Another display not shown here is the Dashboard used to select the figures – previously saved results from the accounts, with or without scaling, for budget preparation; as well as the budgets and actual figures to be used for monitoring.

DEBT ADVICE

Apart from its use for private individuals or for accountants responsible for the personal financial affairs of some of their clients, it is believed that these balancing and monitoring tools could also be extremely helpful for debt advisors.

With knowledge of a client’s financial affairs, a client-budget could be relatively easily established by an advisor using the Balancing tool and readily available statistics about the typical distribution of household expenses.

Particular emphasis would have to be given to putting aside appropriate amounts over a period for reducing the existing debt and balancing this with a plan for tailored, barebones living expenses. The situation could then be monitored by use of DWB accounting and the budget adjusted periodically, as needed by the advisor with client involvement, as time unfolds.

Hopefully the client would see the benefits of this form of financial management so as to be able to continue using it for themselves to achieve a continuing and improved lifestyle once the debt had been cleared.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

There is a real need for the eventual availability of integrated toolsets for personal and household financial management (aka accounting) including the concepts of the budgetary and monitoring support described here. They would preferably be available as online SaaS implementations, for the reasons given in my previous blog. With this, private individuals together with other finance professionals including accountants and debt advisors could be given the means, perhaps for the first time, to really have a chance to relatively easily and effectively gain and maintain control of the personal and household finances for themselves or their clients.

Monday, 20 April 2009

THE WAY-AHEAD FOR THE MANAGEMENT AND CONTROL OF PERSONAL FINANCES

With the second anniversary of the book coming up in August 2009, I thought it might be of interest to put down some of my own ideas about the way-ahead for managing home and personal finances.

By managing and controlling home finances, I am concentrating on the idea of the background activity of knowing all about the state of the finances of a household situation.

From the early days when I started delving into managing my own personal finances, I always believed that this aspect of management was crucial to everything else that followed. The control aspect followed on from the basics of knowing what was going on in the present and how it might have changed from the past – so that there was a starting point for deciding if anything needed to be changed for the future. From this, it was a question of what needed to be changed, by how much and how to do it – and that is where the idea of maintaining the best possible balance came from in relation to a new focus to replace business profits.

I also recognise that there is another very important aspect of financial management which is all about financial products needed by a household – mortgages, loans, insurance, investments and so on - which is what most personal finance websites throughout the world seem to concentrate on.

I would say that management and control of home finances should be the pre-cursor to the selection and purchase of financial products so that affordability and that balance I mentioned can be best brought together.

It will also be vital that proper, appropriate and continuing advice be sought about the type and the choice of particular financial products throughout life; but that is not the concern of this slant on financial management and control.

Historically, most attempts at managing home finances have essentially been fairly ad-hoc – say over the last ten years - until quite recently. Prior to the arrival of personal computing, virtually no one would consider keeping manual accounts for a home or personal domestic situation. At best, hand-written notes would be all that people might attempts in conjunction with bank statements relating to their account at the local bank, indeed if they had one.

With the arrival of home computing, two products made a major (?) difference to the situation – spreadsheets and off-the-shelf personal accounting packages.

Spreadsheets probably made the most impact as they were and are, relatively easy for the homesteader to understand and use. The main sorts of uses would have been bank account reconciliation and simple budgeting as well as for example, analysis of utilities (gas, electricity, water, telephone, etc.) consumption and expenditure.

The accounting packages opened up more possibilities for those with some knowledge of accounting or for those with the necessary sense of responsibility to find out sufficient about accounting to ‘have a go’; and I suppose I fell into both of theses categories!

These accounting packages (and there were and are a number of them still available) were what I think if as bare-bones packages. They arrived ‘empty’ and you could start creating individual accounts as you needed. They were essentially, single entry systems as opposed to business double entry systems and some tried to provide a move towards home accounting with some pre-set categories available for associating transactions with different forms of income or expenses - salary, food, car, holiday etc.

Appreciating that business accounting must have much to offer for personal finances since it had evolved as ‘best of breed’ as the only and legally required way to manage business finances, I decided to follow this route and eventually came up with my new domestic accounting model with a new focus on what I called Domestic Well-Being (DWB). As a model it consisted of a structure for the transactions and associated reports that characterise domestic life – and more information about this can be found in my other blogs and at my website at www.dwba.co.uk .

In the years prior to publishing my book, I had quite by chance, chosen the Microsoft Money product on which to develop and first implement the new accounting model. As a bare bones package, this required that I get down to the intricacies of accounting in order to make it all work.

It was because I found this quite complex that I decided that another approach was needed to address the aspects of accounting that I found difficult and that was going to make it possible for me and others in the future to have any chance of making personal accounting viable. This turned out to be the new naming convention for accounts that I created and associated with an extended version of the accounting equation. By putting more emphasis for transactions on the ‘From’ and ‘To’ an account in order to keep the accounting equation balanced, I was able to get away further away from debit and credit.

Apart from their association with a bank account, I always found debit and credit extraordinarily difficult to visualise, especially for some of the more disparate accounts that might exist in a typical chart of accounts. I appreciate that accountants (like my son) have little difficulty with such concepts because they live and breathe debit and credit for over four years of their professional training; but that is not the same for amateur accountants who might be tempted to try to gain control of their own personal finances.

The problem for these amateur accountants today is that they cannot avoid having to know something about accounting. For a start, they have to purchase an empty personal accounting package and then have to set it all up, creating the necessary accounts, categories, reports and so on. At least with the techniques associated with the new accounting model, understanding of the bookkeeping – entering of transactions – is now relatively easy to understand. [Those who chose to get hold of my book avoid all of this as the attached CD provides everything they need for the particular product that I used so that they can be up and running from day 1 – the details of the starting position can even be added later].

There is an issue with the possible architectures for accounting packages which I discuss more fully on my website. Essentially, the association between the transactions and the components of the Domestic Well-Being structure is achieved by categorisation e.g. in Microsoft Money and by making a single entry system double-up as a double entry system, or by the more business oriented, nominal accounts approach, whereby a separate account is created for each category of income or expense. Two alternative approaches are therefore available but the single new model can be implemented on either of them. This shouldn't be an issue for the users but because the users have to become involved in implementation issues, some packages from this generation of accounting packages are distinctly, user unfriendly.

Again, as described in more detail on my website, I discovered ‘Personal Accountz’ since publishing the book which is an example of a personal accounting package based on the use of double entry and nominal accounts. It is fantastically easy to create and move accounts around in the structure and with ‘grouping’, means that the DWB accounting model can be easily implemented, such that the Domestic Balance Sheet and the Domestic Well-Being Statement (DWBS) that replaces the business Trading and Profit & Loss accounts, is always as up-to-date as the last transaction entered.

However both these solutions, with good graphics and the required reports are still accounting systems and users cannot avoid having to get to know a bare minimum about accounting. The advantage though is the tremendous visibility that is provided about the state of the financial affairs of a household or domestic situation; not only the current situation but with all the past records as a basis for on-going analysis in order to make decisions about how best to improve the situation. For this, budgets assume importance and some systems provide integrated budget capabilities with the ability to set warnings based on chosen levels of spending in selected categories with alarm bells as the limits are approached.

Another feature of the new model is a set of new ratios or factors to replace the over 30 rations used in business accounting. These will be of little use to begin with, apart from internal comparison on a period-by period basis, as it will require the accumulation of a base of statistics so that householders can begin to compare their figures with those of others in a similar situation, rather similar to business norms for different business areas.

What about the future? Well in the last few years, business accounting has and continues to experience a dramatic change towards online accounting. What does this mean? Well instead of buying an accounting package and having to set it all up and periodically update it as a new release is made available, the service is provided as Software as a Service (SaaS).

The software is centrally managed, setup, backed up and recovered, and updated by the vendor as users subscribe to the available services. They can log-on from anywhere and access the various modules needed to conduct their business. Accounting is only one such service and a whole host of other business functions are typically provided such as stock, payroll, invoicing, Customer Relations Management (CRM), Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) and so on.

Security is an important issue since business data is held centrally and requires absolute and guaranteed protection from unauthorised access as well as guaranteed online availability. Private individuals are likely to be even more wary of putting their personal financial data into the ether, or cloud as it is now known!

At the time of writing there are some 30 vendors worldwide providing these SaaS business accounting services. Some of them as new start-ups’ have concentrated on removing or at least hiding some of the mystique of accounting so that non-accountant sole traders, consultants and small business owners can concentrate on managing the business rather than worry about the accounting itself. Others have tended to move existing standalone systems to the online environment and have not perhaps utilised the potential power of modern software to take advantage of online interactivity.

Online SaaS has to be the next move for home and personal accounting!

I am aware of only one online personal finance system today, called Mint. It is a US site and is currently only available in the USA. Its emphasis appears to be the making available of individuals’ financial data so that third party vendors can offer financial products to users – not for me!

The debt crisis in the UK with trillions owed by households and the credit crunch whereby life generally has become extremely difficult for many people, has important implications if its resolution or easing is ever to be possible.

It all comes down to personal responsibility. Those who already have a sense of responsibility have no doubt tried to do something about avoiding or at least keeping debt to manageable amounts. This must involve doing whatever is possible to know about the state of personal finances. If easier ways of gaining control of personal finances became available, then it is most likely that responsible people would start to try to use them in increasing numbers.

How many responsible people are there in the world? I don’t know but surely it is far more than one might imagine – hundreds of thousands, millions – but most likely, a very large number.

There is a niche out there, waiting to be exploited!

For the vendors of online accounting, it would appear to be a relatively simple exercise to produce online versions of their business systems tailored for home and personal use. It would mostly be an exercise of cutting back existing features such as those for sales and purchasing (the heart of business accounting) with a new emphasis on income and expenses. Focus has to move from nominal account numbers to account names and some name changes for the reports. Graphics together with drill-down would assume more importance since the nature of a structure, such as the DWB structure, cries out for this form of summarisation.

For ease of use and with no auditing responsibility, data entry has to childishly simple with emphasis on re-use of previously entered information. Online access to bank statements means that statements from many UK banks can now be downloaded in well recognised formats. I still choose a semi-automated approach in order that I can remain in control of the data in my system and be aware of all the changes that have occurred; it is still necessary for me to associate some of the transactions to categories in the DWB structure but for many of them, the software can make the association so I simply click on ‘accept’ for each one. Bookkeeping is a relatively quick and easy process and might take up to a couple of hours a month – trivial compared to the visibility achieved on the state of home finances.

A first evolution of online accounting for domestic use would probably still look quite like an accounting system but could and should be very workable for the end-user subscriber. Publicity and advertising will be an important area here in order to attract people to this powerful new capability as an online service. Bookkeeping could be done on the way, to and from work.

A next generation service should evolve to a home financial management system. Accounts per se would be well hidden and the user would only have to relate to concepts such as assignment of expenses to categories and decisions on quantities of appreciation or depreciation on certain assets, perhaps once a year.

The focus would be on the results in terms of the reports, comparisons and graphical interpretations from the underlying data. The results of the decision making process would imply support for budgeting which is in need of improvements and could perhaps be linked to some independent systems now already available.

In time, it would be appropriate to see domestic accounting recognised by the accounting authorities as a branch of accounting in its own right, alongside business accounting.

The management of personal finance is so important today in the light of the debt crisis that there ought to be some degree of national, social responsibility alongside personal responsibility, to help people minimise their exposure to debt as well as assist with its management and reduction where it has already occurred.

The users of online personal accounting would not only be the end-user homesteader, but accountants looking after the private finances of their clients. Links to Income tax filing would also be a useful adjunct.

People, both voluntary and from business concerns, responsible for analysis and advice on financial hardship, particularly debt recovery would represent a further group of potential users.

There would be new opportunities in education, both at the school and college levels, as well as for adult education.

In conclusion, I believe that the time has arrived for personal accounting to be brought out in the open in comparison to its somewhat chequered and hidden past where it has been the province of the enthusiastic and dedicated amateur – witness the forums associated with the various personal accounting software packages.

Families throughout the world should be the beneficiaries with hopefully, better and more contented lives based on the income available to them.

Tuesday, 3 February 2009

DWB ACCOUNTING - SOME THEORY

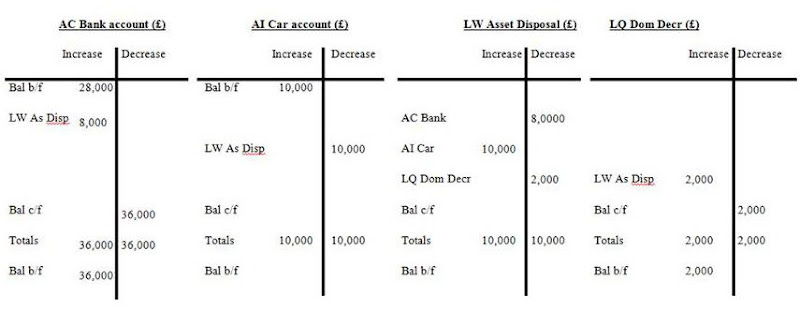

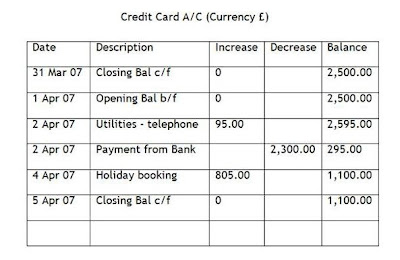

We had a first look at Reports in my last blog so it is now appropriate to take a step back and talk a little bit about some accounting theory in the context of the Domestic Well-Being (DWB) accounting model.

You might find the theory a little intimidating at first but it is here for those who wish to really understand what is going on and to make it easier to atually do. I will summarise the important parts at the end and all you will actually need in order to start doing this sort of accounting is to be able to look at and interpret some fun, memory joggers which tie the theory together!

In developing the DWB accounting model, my overriding aims were focus and simplicity. My earlier attempts to use business accounting methods for personal accounting had proven very unsatisfactory because I realised that the business accounting model had the wrong focus for home use and it was all too difficult to understand and to do, on a day-to-day basis.

Since I wanted to run my accounts in a continuing way, year after year, and I wanted to capture the complete household financial picture, I decided that business style double-entry techniques were important (more about that in a moment) and had to be a part of the new accounting model. Because of this, I needed to find an easy way to remember which accounts to use whenever transactions were entered into the accounting system and which side of an individual account did each entry go; and was it an addition, or a subtraction?

So the DWBA model includes not only the new focus and methods to make it all work, but a set of corresponding supporting techniques including some new terminology, naming-conventions and some memory joggers. In this blog, space and time permits only an overview of the theory but the intention is to provide sufficient to convince you that there might really be some mileage in further investigating DWB accounting.

Business accounting is plagued with words that only accountants probably ever feel really comfortable with. Words like capital, equity, asset, liability, debit, credit, income, expense and many more, are not easy to take on board. Partly because we hear some of them in everyday life, particularly debit and credit, in contexts which we may not truly understand, we can end up with an incorrect idea of what some of these concepts really mean. In fact we cannot avoid all the words but with some targeted theory, I have found that it can be made to make a little more sense and with some aide-memoires, it becomes quite ease to understand what is going on behind the scenes in accounting.

The adapted background theory which I think is sufficient to meet that first aim, of simplifying accounting, covers the following features:

- 1. Accounts and overarching types – Asset and Liability

- a. An Account

- b. Asset Accounts

- c. Liability Accounts

- 2. Scope of Accounts

- 3. Double Entry concepts

- 4. Domestic Accounting Equation (DAE)

- 5. Working Accounts

- 6. Categorising Changes

- 7. Account Naming Conventions

- 8. Making Use of the Account Types

- 9. Keeping the Accounting Balance

- 10. Conquer From/To, Debit/Credit and Income/Expense Relationships

- 11. Bookkeeping and Categorising Information

- 12. Summary

1. Overarching Account Types

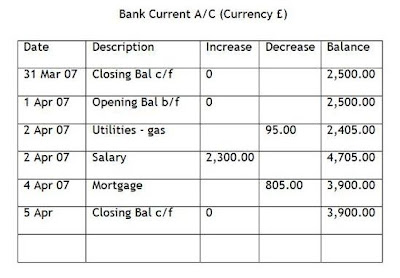

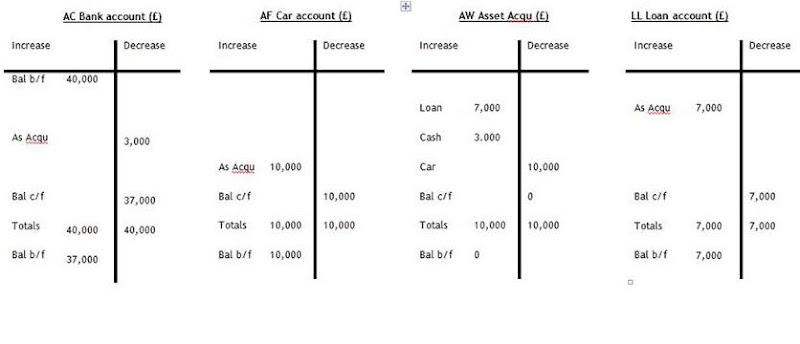

a. An Account

Starting at the beginning, we should realise that a single account is simply a time-sequenced list of changes to some particular area of financial activity going on in the background. An account will normally have an account title for the area of interest, such as cash, current bank, savings, car loan, main residence and so on. It is important to realise that an account is always associated with some sort of value.

This value may be for money as ‘liquid’ cash or for amounts stored in current or different bank savings accounts. An account may also be created to provide a record of the changing value of the home, car or a holiday, where the monetary value of the designated object might change over time, perhaps with gains, losses or appreciation and depreciation.

The transactions making up or entered into an account will address changes to the amount of its balance and each typically includes a date, a description and/or a reference to the activity causing the change, as well as the actual value in a separate column according to whether it is an increase or decrease of any amount held in the account. Computerised accounts will often include a running total to show the changing balance of the account after each transaction is applied.

Printed account extracts will usually also include the opening and closing dates and balances; these can be made obvious in the accounts by including zero-balance transactions at the start and end dates of a period with descriptions such as Opening Bal b/f (brought forward) or Closing Bal c/f (carried forward).

This simplified account in our accounts for a current account at a bank with a minimum number of column headings, shows just a few entries before the end of the UK financial year on the 5th of April.

It is important to distinguish between increasing and decreasing amounts of change to an account compared to the corresponding changing value in the account because these will not always be the same, as we will see shortly.

b. Asset Accounts

The balance of an asset type account where positive amounts represents positive value is typically used to accumulate financial information about cash deposits, a house, a car or an investment. We will see later that asset accounts can also be used for some special information in so-called Working and Quasi-asset accounts. That salary increase above of £2,300 is known as a debit or income entry because debit always means increasing value whilst in contrast, a decrease in value –for the gas or mortgage payments above – is known as a credit or expense entry.

The words income and expense here are types of entry related to value (like debit and credit) and should not be confused with salary as a particular form of income or the purchase of food as a particular sort of expense. Quite obviously, you will enter income received into one of your bank accounts into an appropriate asset type account in your own accounts, with a debit or income type entry. This is because it represents increasing value from the point of view of the entity which your set of accounts represent, which is you as an individual person or your household, if that is your situation.

To summarise our first rule; debit or income in an account represents increased or positive value whilst credit or expense represents decreased or negative value.

c. Liability Accounts

Another example of an account shows some entries for one of our credit cards. All the entries look basically similar to the last account except for one essential fact:

The essential difference is that this account represents financial activity relating to things purchased ‘on credit’ so it is all about value owed to someone or some organisation - a liability.

The Opening Balance of (+) £2,500 in this credit card account shows that we had already obtained credit of this amount relating to objects that we had purchased previously, less any payments we had already made to reduce our debt or amount owed. We have an outstanding charge of £2,500 by being given credit of this amount by the credit card company. We are in indebted to that organisation with a debt of £2,500 and we are one of its creditors who owe the card company this same amount.

As we make more payments ‘on credit’ we can see that in this type of account they are increasing positive numbers representing amounts of charge, more liability and therefore less overall value in our account. These additions go to increase the amount that we will have to pay back to the card company at some future time. Each of these transactions representing increases in liability implies less value and by the accounting rule, is therefore a credit or expense entry into that account.

A payment from our bank (a credit or expense entry from an asset type account) as one of those repayments is shown as a decrease in this Credit Card liability type account because the amount that we owe to the credit card company is reduced by this (positive) amount. Our liability is in effect, reduced by £2,300 and so this entry is a debit or income entry in a liability type account, signifying an increase of value because it reduced a liability – a double negative in mathematics! This is an example of a proper credit and debit entry pairing which as we will see, characterises double entry and maintains value in the whole collection of our accounts.

This account is an example of a liability account. A liability account is used to store amounts of value that are owed to someone or some entity and even to another account in our so-called, book of accounts and so they use positive numbers to represent negative value. Their positive balance and any increases (credit/expenses) represent negative value since more of a liability means that more is owed to whatever the account represents. Likewise, decreases or reductions in its positive balance imply less liability and therefore more value (debits/income). I refer back to that comment that I made about distinguishing between increasing amounts and values. In liability type accounts, more implies less! More of an amount in this account (an increase) represents less value (a credit or expense) whilst reduced amounts imply less liability and therefore more value.

Having introduced these two examples of different types of account, it is very important to distinguish between what I call overarching types of account versus the use to which these two types of account may be put, usually indicated in the account name.

So we have two overarching types of account or tools in our accounting toolbox. An asset type account is simply an account where a positive balance means positive value whilst in contrast, a liability type account is one where a positive balance implies a negative value. I shall come back to this distinction shortly when we begin to see what types of accounts are used for what purpose in an accounting system.

2. Scope of Accounts

We use accounting and accounts to model financial activity. In business where large organisations may have multiple departments or divisions, we can recognise that accounting may be applied to company-wide financial activity or separately, for the different sub-divisions. An accounting system therefore has a concept of scope or a boundary which determines the extent of financial activity to which it applies.

Similarly for a home, personal or domestic household situation, we can envisage that the financial activity could be considered from different levels of scale. Typically, a user of a home accounting software package might limit its scope to cheque reconciliation where the extent of the activity would be restricted to just that of the current account at a bank. For this, a single account would suffice and could be achieved with a personal accounting package or even a simple spreadsheet table. Where a family might have a current account as well as one or more savings accounts and some credit card accounts, they may wish to extend their accounting activities to include all these aspects of their home finances but still not address their complete financial picture.

We therefore have a concept of an accounting system which addresses differing scopes of all the financial activity within some specified scope or boundary.

In business, be it for a sub-division or subject area such as human resources – wages, salaries, taxes, national insurance, pensions, etc. accounting legally has to cover all aspects of financial activity within the specified scope; and all activity has to be covered, even it is subdivided into separate compartments with corresponding scopes and separate accounting systems.

Back to the domestic situation, financial activity obviously includes the bank and credit card arrangements we have already discussed, including all the increases and decreases being applied to them. However we mostly have some household assets (not thinking of asset accounts yet) such as a home, one or more cars, furnishings, appliances, maybe a caravan or time-share or even a boat as well as financial investments such as assurances, stocks, bonds and so on. We think of an asset, as opposed to expendables, as something having some residual value which maybe realisable so that we can get some money back in exchange for its disposal. We may never know that value until we achieve a sale but at least we can estimate its value as it changes over time, either up or down, in order to know the estimated and changing value of all our assets.

Another side of personal financial life relates to mortgages and loans, as well as those credit charges we already looked at. These are our personal liabilities or debts of different types.

Our day-to-day outgoings on food, utilities, health, transport, education, holidays, pensions, etc. actually represent the largest and most influential part of our household financial activity. This represents the bulk of the dynamics or changing part of this activity in contrast to the slow-to-change, relatively static personal assets and liabilities.

To really manage and control our personal or household financial activity we need to look at the complete financial picture. This means that we need to understand and know about both the static and dynamic parts of our domestic financial activity. This is because proper control of our finances has to consider all its aspects, our assets, our personal liabilities and the constant changes made up of the monies we receive and the constant stream of outgoings or decreases which characterise our domestic life.

The scope of our interest should be total and likewise the scope of the accounting system we build to model it should be all-embracing. Instead of just a few accounts to model our banks and credit cards, we should try to model all our changing assets, our obligations to others as mortgage debts, loans and charges, as well as our day-to-day increases and decreases required to stay alive.

By doing this in a way that is tailored to the characteristics of our household financial activity – such as by use of the DWB accounting model – we can obtain the visibility on it all to effectively gain and achieve the control we seek.

3. Double Entry Concepts

Double entry accounting is a simple concept having two implications:

It represents a total view of the financial activity within some designated scope or boundary that defines our accounting system.

It utilises two postings or entries in our accounts for each financial transaction to ensure that the complete set of accounts remain in financial and mathematical balance.

The total view requires that an extra account is created and maintained to store the total worth of the financial system or area of interest within the designated scope.

Double entries in bookkeeping where transactions are entered into the accounts require that value is ‘conserved’ by matching pairs of debit (Dr. gain) and credit (Cr. loss) postings. An increase in value must always be matched in the accounts by a corresponding decrease in value. We will see in a moment how this pairing of postings or entries is achieved where I emphasis 'From' and 'To' rather than Dr/Cr.

4. Domestic Accounting Equation (DAE)

I find that double entry accounting can best be explained by the use of the ‘accounting equation’ which I have adapted for domestic use.

Hopefully, accepting that the balances of all the accounts representing the finances of an entity must somehow be related, schooldays remind us that related numbers is what equations are all about! Where perhaps 20 numbers represent the 20 balances of these required accounts, we should be able to relate these 20 numbers meaningfully in an equation in some way.

The traditional Accounting Equation shows the financial relationship as:

Assets - Liabilities = Capital value or Shareholders or Owners equity.

The basic version of the Domestic Accounting Equation (DAE) is:

Assets - Liabilities = Domestic Wealth

In order to manage our finances with double entry accounts, we will need to create accounts for all our assets using those asset type accounts as well as sufficient accounts of the liability type for all our different personal debts or liabilities, plus at least one more account for our Domestic Wealth. So in terms of the Domestic Accounting Equation (DAE), we can say where a/c stands for account:

All personal Asset a/c balances (of the asset type) - All personal Liability a/c balances (of the debt type) = Domestic Wealth a/c balance

Thinking about it, the value of domestic wealth represented by the value of the assets less the value of all the personal debts is owed to the eventual beneficiaries of the household or individual’s estate. After death, the executors have to pay off the debts from the assets and what is left, the Domestic Wealth, will be shared out amongst the beneficiaries - so the domestic wealth is a sort of liability from the viewpoint of the entity represented by the set or book of accounts, an individual or a householder.

The domestic wealth is owed to the beneficiaries and therefore should logically reside in a liability type account. I decided that I needed to distinguish between personal liabilities and liabilities of the estate so that is why I defined ‘quasi’ liability accounts of the liability type to be used to hold the Domestic Wealth and some other associated accounts to handle changes to Domestic Wealth. Compared to true or personal liabilities held in current and long-term liability accounts which can be considered as 'bad' liabilities, Domestic Wealth can be considered a 'good' liability and so the set of quasi-liability accounts in DWBA distinguishes or highlights these good liabilities - the greater the positive amounts or the less of the corresponding value in them, the better!

Considering changes over some period, increases from salary or growth imply more wealth so logically; those increases should also be stored in some sort of liability type account, alongside the Domestic Wealth account. So we also need one of these quasi-liability accounts for accumulating domestic increases.

Conversely, decreasing amounts resulting from expenses such as on food, drink, hobbies and holidays, as well as depreciation and losses, should also logically be stored in a separate account. They mostly come from decreases in either one or other of our asset type bank accounts or one of our credit card liability type accounts. To store decreases of positive amounts of assets or positive amounts of credit, we need an account to accumulate these positive numbers and an asset type account is the appropriate sort of account to use. Remember that a decrease in a bank current asset account (credit) can be matched by an increase in another asset account (debit) or a decrease in a liability account (also a debit – creating more value).